A Web-Based Resource on China-Related Federal Prosecutions of Economic Espionage and Trade Secrets

The number of Asian Americans who are subject to or affected by federal espionage and trade secret investigations and prosecutions is a matter of growing concern.

Three recent failed prosecutions involving four Chinese American scientists highlight the significant void of a one-stop information resource to understand the historical trend and the current status. As the accused and their families suffer emotional stress and financial, professional and reputational ruin from the false accusations, concern and fear spread in the Chinese American community about the apparent pattern of profiling and discrimination by the U.S. government.

How many similar cases are there? Are there other unjustified cases? What has been the trend and pattern in law enforcement? Is there disparate treatment? Are there lessons that the community can learn and act on as a result? Should the government take a different approach? Without basic facts and reliable statistics, even simple questions become difficult to address.

The government has so far not provided a satisfactory response to the many calls for explanation, apology and independent investigation. A fact-based resource has now been created to enhance community understanding, promote transparency, hold the government accountable, and ensure fairness in the American justice system.

Economic Espionage and Theft of Trade Secrets

Laws currently used by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) to prosecute violations of economic espionage and trade secrets generally fall under three categories.

First, the Economic Espionage Act (EEA) was enacted in 1996 to provide two offenses:

- 18 U.S.C. § 1831 applies to economic espionage with knowledge or intent to benefit a foreign nation

- 18 U.S.C. § 1832 applies to theft of trade secrets with knowledge or intent that will injure the owner of trade secret

Second, export enforcement and embargoes are usually covered by:

- AECA, the Arms Export Control Act of 1976

- IEEPA, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977, used to extend the regulations of the Export Administration Act of 1979 covering export items for commercial and dual military purposes

- ITAR, the International Traffic in Arms Regulations covering export items for military purposes

Third, there is a wide set of alternative or additional charges that the U.S. Attorneys may apply, depending on the individual case. Among the U.S. Code coverage are: Unauthorized Disclosure of Government Information, Including Trade Secrets, by a Government Employee; Computer Fraud and Abuse Act Fraud Scheme; Unauthorized Obtaining of Information; Intrusion; Mail/Wire Fraud; Foreign/Interstate Transportation of Stolen Property; Money Laundering; False Statement; Obstruction Of Justice; and Forfeiture.

The U.S. government intensified its efforts on economic espionage and theft of trade secrets in 2012 with the enactment of:

- the Foreign and Economic Espionage Penalty Enhancement Act, which increased penalties for foreign and economic espionage under section 1831

- the Trade Secrets Clarification Act, which expanded the scope of trade secrets covered under section 1832

The National Security Division (NSD) was created in the U.S. Department of Justice in March 2006 to combat terrorism and other threats to national security.

In a nationwide television broadcast (CBS 60 Minutes) on January 17, 2016, DOJ claimed that China’s “corporate espionage constitutes a national security emergency, with China targeting (thousands of U.S. companies in) virtually every sector of the U.S. economy, and costing American companies hundreds of billions of dollars in losses — and more than two million jobs.”

The Federal Bureau of Investigations (FBI) reported that the number of economic espionage and trade secret cases increased by more than 60% from fiscal year (FY) 2009 to the end of FY 2013. There was again a reported 53% increase in these cases from 2014 to 2015. The precise number of cases is classified, but it is quoted to be “in the hundreds.”

In addition to the FBI, economic espionage and theft of trade secret cases are also investigated by more than 10 federal agencies, including the Homeland Security Investigations [formerly Immigration and Customs Enforcement], the Department of Commerce’s Bureau of Industry and Security, and the Pentagon’s Defense Criminal Investigative Service.

With the stepped-up efforts by the U.S. government to address alleged economic espionage activities by China, innocent Asian Americans, particularly Chinese Americans, have been affected by the sheer number and aggressive nature of the investigations and prosecutions, causing serious damage to the careers, reputations and financial situations of the persons involved. They also cause rippling effects in the Chinese American communities, setting off many calls and petitions for DOJ to explain its approach and conduct independent investigations about the failed prosecutions and its policies. There has not yet been a satisfactory response.

While we all support the government’s effort to prosecute violators of economic espionage and theft of trade secrets laws, it is equally important that the American justice system protects innocent individuals and provides balanced fact-based information to the public.

FedCases Webpage and Preliminary Results

As a community service, a new information resource has been created in the form of a webpage. The inaugural version of FedCases (http://bit.ly/FedCases) is a complete collection of all known China-related EEA prosecutions of Asian Americans and Chinese Nationals since the enactment of EEA in 1996. There are 50 cases in the current collection, covering the period of 1996 to January 2016, with 3 cases in 2006, 2008 and 2009 respectively yet to be fully confirmed for addition.

Preliminary results based on these 50 cases are presented below. They are subject to further interpretation, verification, validation, and refinement by additional experts, professionals, and the public.

While the following five sets of descriptive statistics do not immediately answer all the questions raised in the introduction of this blog, it is hoped that they will stimulate discussions for the next level of development and analysis and lead to some answers.

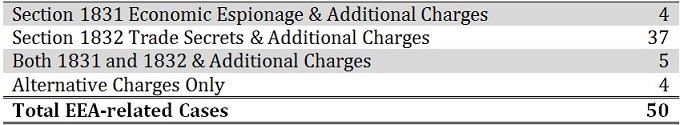

1. Number of Cases by Type of Charges. According to the type of charges made, the 50 EEA cases are placed into four categories in the following table:

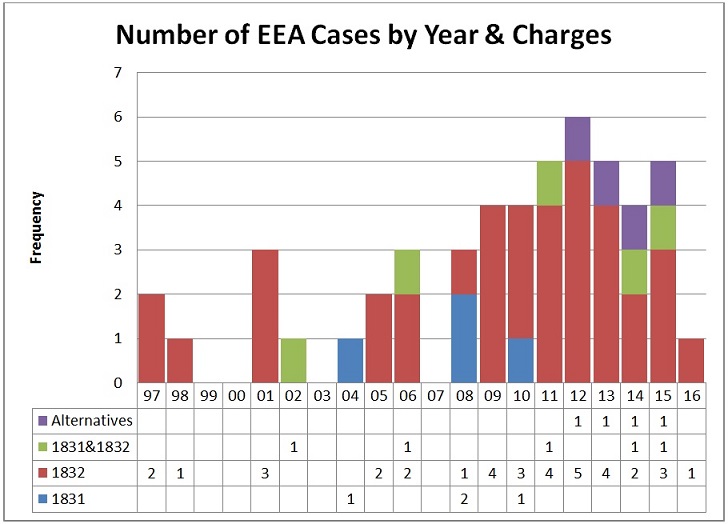

2. Number of Cases by Year. The chart below shows that the number of cases has increased from the annual range of 0-3 cases during 1997-2008 to the annual range of 4-6 cases for 2009-2015.

The exclusive use of alternative charges instead of section 1831 or 1832 by DOJ, while publicly describing them to be espionage and theft of trade secret that benefit China, appears to be a recent trend since 2012 according to these 4 cases:

- 2015 – Temple University professor Xiaoxing Xi; U.S. citizen; accused of wire fraud for the benefit of China; case dropped by the government prior to trial

- 2014 – National Weather Service hydrologist Sherry Chen; U.S. citizen; accused of theft of U.S. Government property, accessing restricted U.S. Government files to benefit China, and making false statements; case dropped by the government prior to trial

- 2013 – Medical College of Wisconsin research scientist Huajun Zhao; Chinese National; accused of stealing cancer data for China and making false statement; he pleaded guilty to accessing a computer without authorization and was sentenced to time served

- 2012 – Sandia Laboratory nanotechnology scientist Jianyu Huang, U.S. citizen; accused of taking unauthorized government property (containing no classified information) to China and making false statement; he lost his job, and was sentenced to one year and one day in prison

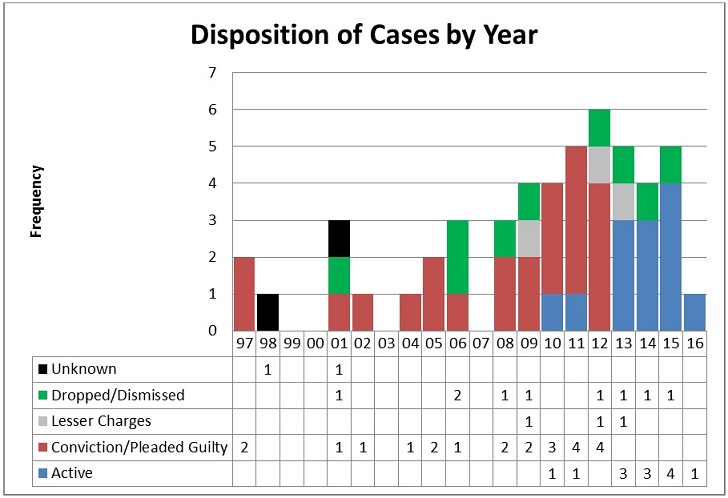

3. Disposition of Cases by Year. Among the 50 EEA-related cases, 13 are still active. Two (2) of these active cases in 2010 and 2011 involve a total of 3 fugitives although the remaining defendants have pleaded guilty or were convicted. Two other active cases were featured by the CBS 60 Minutes Program on January 17, 2016:

- 2014 – PLA Cyber Espionage Against U.S. Corporations and a Labor Organization

- 2013 – Theft Of AMSC Trade Secrets

Of the remaining 35 cases that are closed, 9 (25.7%) were dropped prior to trial, acquitted and dismissed during or after trial, or had a finding of not guilty; 3 (8.6%) were reduced to lesser or other charges no longer related to trade secrets; and 23 (65.7%) were either guilty pleas or full or partial convictions. A case deemed “closed” here may still be under appeal.

Two (2) out of the 50 EEA-related cases dating back to 1998 and 2001 have disposition which are not yet known. As previously mentioned, up to three cases may still be added to the total number of 50 cases upon confirmation.

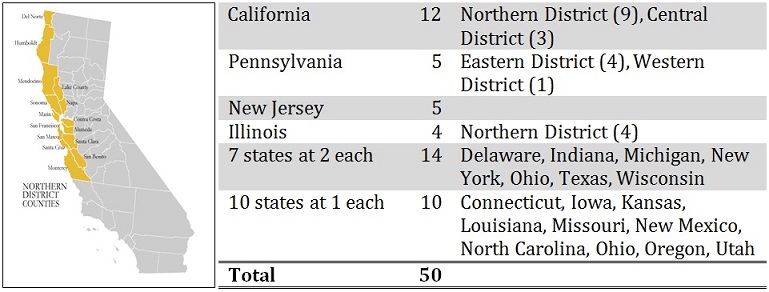

4. Number of Cases by State. The Northern District of California, covering the Silicon Valley, has by far the highest number of cases at 9.

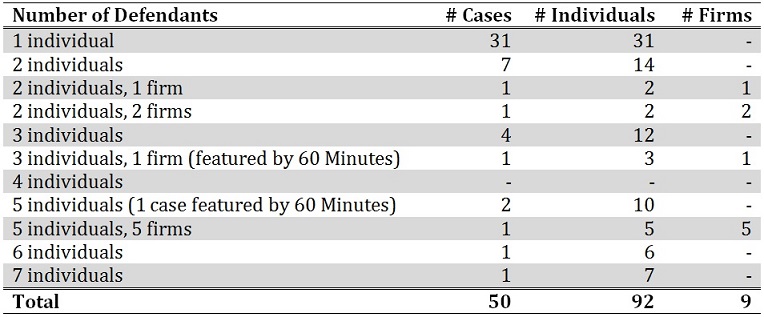

5. Distribution by Number of Defendants. The 50 EEA cases covered a total of 92 individuals and 9 firms. Thirty one (31) cases had only one defendant. One case has as many as 7 defendants; another case has 5 defendants and a group of 5 firms.

FedCases is created as a fact-based resource for research and analysis. It is a work in progress and a labor of love. Efforts will continue to add new cases, complete entries, update status, and improve its content. Community participation and crowd contribution are also invited.

A complete list of references and sources of information used to create FedCases is given in http://bit.ly/AAProfiling.

Acknowledgements and Disclaimer

Special thanks to these and other unnamed contributors of the webpage: Steven Aftergood, Albert Chang, Alice S. Huang, George Koo, Thomas J. Nolan, Daniel Olmos, Aryani Ong, Navdeep Singh, Peter J. Toren, Cheuk-Yin Wong, and Peter Zeidenberg.

This is a personal blog not associated with any organizations. Neither the contributors nor I can totally assure or be responsible for the specific contents of the website. They are based on best efforts and publicly available information that are shared as a resource.

Appendix: Process to Create FedCases

The creation of the inaugural version of FedCases began with these primary information sources:

- Publicly available “fact sheets” issued by NSD since 2006. The most recent version is dated August 2015

- An analysis of 137 federal prosecutions under the EEA from 1996 to July 1, 2015, conducted by Mr. Thomas J. Nolan of Nolan, Barton, Bradford and Olmos LLP (the Nolan list; http://bit.ly/NolanList)

- Online press releases by the 94 offices of U.S. Attorneys, FBI announcements, media reports, public access systems, and similar announcements and electronic sources

The Nolan list of 137 cases is reported to be the result of an exhaustive search of all known prosecutions under section 1831 or 1832 since the inception of EEA in the Public Access to Court Electronic Records (PACER) system for all 94 U.S. District Courts. An earlier version of the Nolan list with 122 cases was included as part of the comments by the Federal Defender Sentencing Guidelines Committee to the United States Sentencing Commission on The Foreign and Economic Espionage Penalty Enhancement Act of 2012.

The process of creating FedCases followed these basic steps:

- Cases that appear to be related to China, Chinese Nationals or Asian Americans are extracted from the NSD “fact sheets,” which present select export enforcement, economic espionage, theft of trade secrets, and embargo-related criminal prosecutions since 2006. The latest available version is August 2015

- An electronic search of the press releases and announcements of the 94 offices of the U.S. Attorneys was made to identify similar cases available at the end of 2015

- A similar approach is used to extract EEA-only prosecutions from the Nolan list covering the period of 1996 to July 1, 2015

- These results are matched and analyzed to yield 37 cases in common. According to the identification number used in the Nolan list, they are: 1, 12, 23, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 34, 37, 39, 40, 44, 47, 57, 64, 65, 67, 68, 77, 83, 85, 106, 108, 109, 110, 111, 118, 119, 120, 121, 122, 126, 127, 135, 136 and 137

- Three (3) EEA cases announced after July 1, 2015 are added, including the GSK Biopharmaceutical case on January 20, 2016

- Four (4) cases are added, as discussed previously, for their exclusive use of alternative charges as economic espionage. Their First Date identifications in FedCases are 2012/06/05, 2013/04/02, 2014/10/20, and 2015/05/21

- Six (6) cases prior to July 1, 2015, but do not appear in the Nolan list, are added. Their First Date identifications in FedCases are 2006/05/10, 2006/12/13, 2012/09/04, 2014/05/19, 2014/12/09, and 2015/05/08

- The collection of 37+3+4+6 = 50 cases is then integrated to create FedCases. Three (3) cases in the Nolan list have not yet been added because of potential entry errors or lack of confirming information at this time. Their identification numbers are 9, 76, and 107

Substantial efforts have been made to verify and validate these cases, including the identification of confirming sources and relevant links, such as

- An analysis of 124 federal prosecutions under the EEA from 1996 to September 1, 2012, conducted by Mr. Peter J. Toren of Weisbrod, Matteis & Copley

- The February 2013 White House Report “Administration Strategy on Mitigating the Theft of U.S. Trade Secrets”

- Online media reports, official announcements, public access systems, and similar electronic means

- Comments and contributions by individuals and community organizations such as the Committee of 100 and the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association

Among the 50 EEA cases, only 19 (38%) have been mentioned in the NSD “fact sheets.” Most of the cases not included in the NSD “fact sheets” but derived from independent sources either date prior to 2006, or more recent (since August 2015), or involve acquittals, dismissals, finding of not guilty, or reduced charges no longer covering trade secrets.

The overlap between EEA cases and illegal exports appears to be relatively small at 3 out of 50 cases (6%).